If there’s one classic car race that is special to me, it’s the Monte Carlo rally. When I was seven, I moved to Monaco with my family, and in the three winters we were there, my father and I went up into the French hills above the Principality where the race takes place to watch it.

Of course in those days, watching rallies from the road side was a bit more intense than now, given there were practically no safety measures whatsoever. In terms of childhood memories that stick, I can thus tell you that standing right next to the road in complete darkness and hear an engine roar building long before you see the headlights, and then have the car pass one meter before you at a speed that if it hit you, would send you fly all the way back down to the beach – that’s definitely one of them!

First run in 1911 when it was inaugurated by Prince Albert 1, the Monte-Carlo Rally actually counts as the oldest rally in the world, and no doubt also as one of the most famous. The organization of the race has since the beginning been the responsibility of the Automobile Club de Monaco, in turn founded as early as 1890.

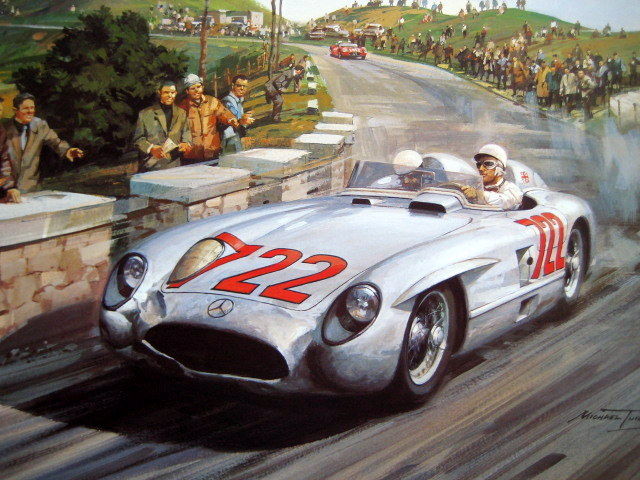

As with so many races in the old days, things were a tad less organized. The 23 cars in the first ever race started from nine different locations in France, with a certain Henri Rougier, who was the main dealer for his car brand Turcat-Mery, starting with some others in Paris. From there they drove the more than 1000 km to Monaco, where Rougier was judged as winner in his Turcat-Mery 25HP.

It’s a bit unclear if he arrived first as the judging also included some rather arbitrary categories such as elegance of the car and its condition at arrival. Far from everyone apparently agreed with Rougier’s win, but it didn’t change the result. A gentleman named Justin Beutler finished third but would win the race the next year, after which there wouldn’t be any further races until 1924.

Moving forward to the post WW2 period, the race was resumed in 1949, with an array of different cars and drivers winning it in subsequent years. A Hotchkiss Gregoire is perhaps not what we imagine under a rally car today, but it was part of the winners, as were notably also the Lancia Aurelia GT and the Jaguar MK VII. And then came the Swedes…

In 1962, Saab entered the Monte Carlo Rally with the Saab 96, driven by Erik Carlsson. He was one of the world’s best rally drivers in the early 60’s, and in Sweden carried the nickname “on the roof”, since that was where he had landed his car during a race early in his career.

He was however also known as Mr. Saab as he would never drive another brand, and he won the Monte Carlo Rally in 1962-1963, finishing third in 1964. That year, the next car that would dominate the race in the coming years won for the first time – the Mini!

Mini would win three races officially in the coming years, and four years unofficially. In 1966, no less than three Minis were the fastest, but they were all disqualified for having incorrect headlights. That was apparently a bit of a scandal, but it only increased the Mini’s popularity over the coming years.

Since the start, the Monte Carlo Rally had remained a so called concentration rally, meaning cars would start at different locations at roughly equal distance to Monaco, around which there would be a few special stages. This would be the case all through 1991, making the rally very special – as did no doubt the fact that it was run in the winter when there would typically be snow in the final mountain stages.

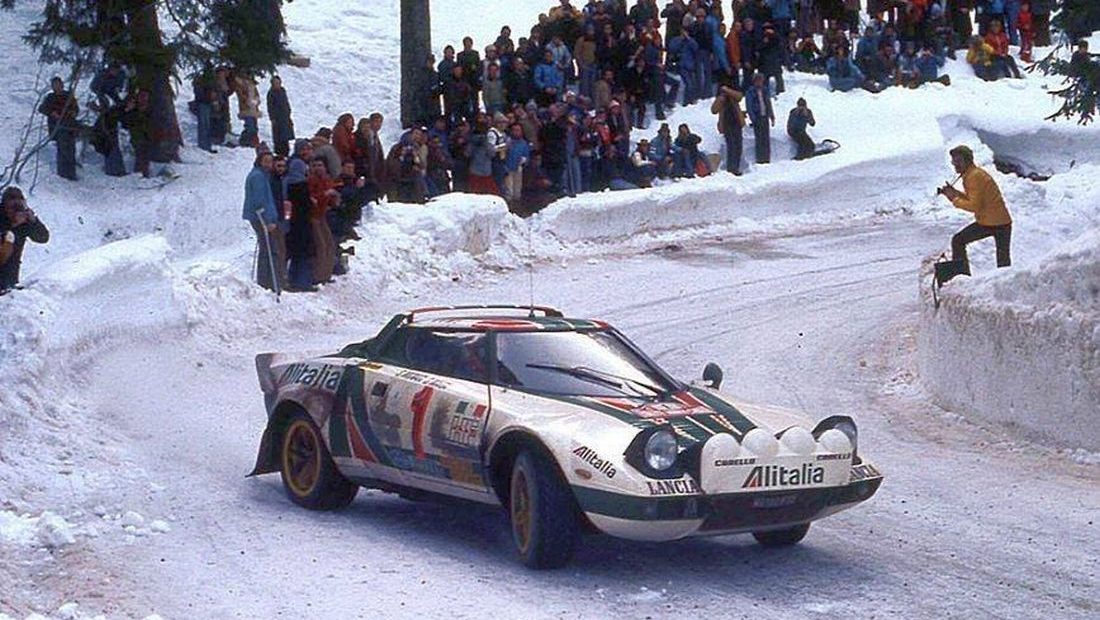

It was these stages, especially those run at night, that captivated me in the late 70’s and early 80’s. And the stage that has always been the most captivating is the one on the 31 km between La Bollène-Vésubie and Sospel, passing the famous Col de Turini. In some years it’s been run at night, officially referred to as “the night of the long knives”, a reference to the headlights I mentioned initially cutting through darkness.

In some years when spectactors have felt there wasn’t enough snow on the road, they’ve brought shovels to add some from the side of the road. That notably led to both Marcus Grönholm and Petter Solberg crashing heavily in 2005, being surprised there was all of a sudden snow on the road. That’s the Monte Carlo Rally!

In the late 70’s, the Lancia Stratos was by far the coolest car, and also won the rally a couple of years. The king of the rally in this period was however German Walter Röhrl, who won the rally four times – in four different cars! In the 80’s it was then all about the Audi Quattro, before recent history has seen a mix of the same cars winning other rallies.

With a lot of non-French drivers dominating the rally over earlier decades, in the 2000’s it’s mostly been about Frenchman Sébastien Loeb and his countryman Sébastien Ogier. Loeb won a total of eight races since the 00’s, and Ogier no less than nine times since 2009, making him the most successful Monte Carlo driver in history.

The next Monte Carlo rally will be run on 21-24 January 2024, and includes the famous Col de Turini stage. If you happen to be in southern France then, you know where to go!

If you’re not, check this link for a 5-minute video showing Walter Röhrl driving the Col de Turini in an Audi Quattro on its 30-year anniversary, perfectly illustrating that neither the car, nor him haven’t lost the magic! And if that’s too old for you, you may want to see Sébastien Ogier giving lessons in inspired driving in this year’s rally by clicking here!