In a post back in August that you can find here. I made a very unscientific comparison of the depreciation of EV’s vs traditional ICE cars. The conclusion was on one hand that EV depreciation is indeed as bad as it feels, but also that ICE’s depreciate quite heavily as well and seemingly, far more so than they used to. I’m pretty certain that most of you reading this blog agree that “peak car” is pretty far behind us, and the conclusion from the comparison therefore seemed to make the case for hanging on to your existing jewel for a while longer.

That said, the thought has been nagging me that I may be missing out on something. After all, billions after billions has gone into the development of this new car concept referred to as of EV’s, and these cars cost half a fortune as new. Surely it must have led to something that is the next step in automobile development? To me, the car my thoughts have focused on is the Porsche Taycan, hailed by many as the best EV out there, and no doubt the best-looking.

When talking about the Taycan, like most people I initially preferred the station wagon. With time though, the sedan has kind of grown on me and today, I find it at least as stylish as its equally good looking EV sibling, the Audi e-tron. As mentioned in the post back in August, although prices have started to stabilize, there’s definitely still deals to be made, so when I saw a well equipped Porsche Taycan 4S being advertised by a Porsche dealer close to me for CHF 64.000, from an original price of close to CHF 180.000 four years ago, I figured it was worth checking out.

Given this is not an EV blog, it’s perhaps useful to remind us of the history of the Taycan. It was launched as a 2020 model in late 2019, initially as Turbo and Turbo S (leading to a pretty meaningless discussion on how on earth they could be called Turbos when they didn’t have one…), later complemented by the 4S and the entry level only called Taycan. The station wagon was launched a year later on an extended platform, either as a sleek Sport Turismo wagon or as Cross Turismo with a slightly more rugged look. At least here in Zurich, it’s the Cross Turismo you see most of on the road.

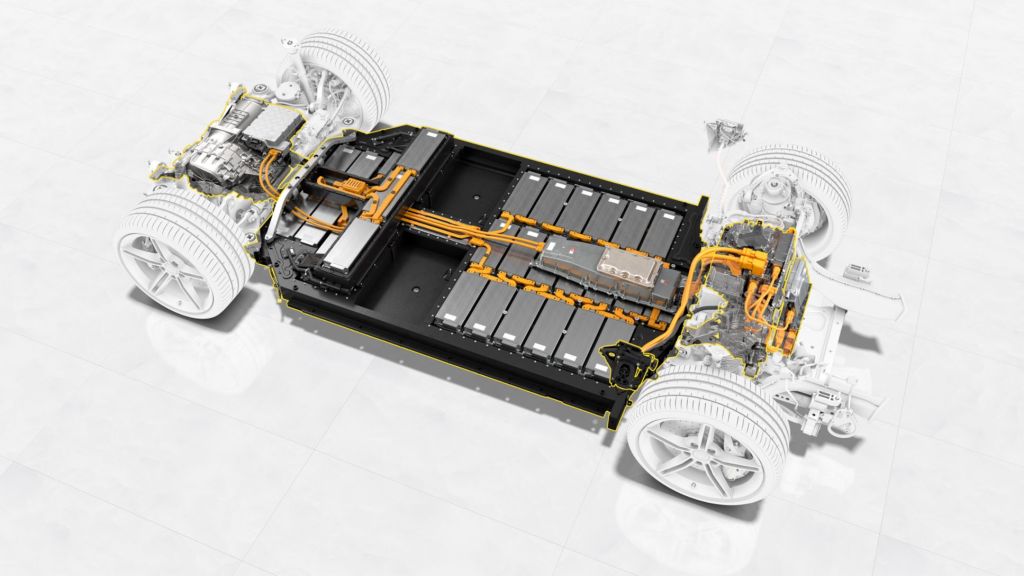

The Turbo and Turbo S came with the so called Performance Plus battery as standard, a 93 KwH pack giving them a theoretical range of around 430 kms. The 4S however came with a smaller, 79 KwH pack as standard, with the larger pack being optional. Given the smaller battery pack only has a realistic range of around 350 kms, that option is pretty critical for having any kind of secondary value on your Taycan. The good news is however that all Taycans run on an 800V platform, meaning charging times are among the best in the business. The bad news, which depending on where you live is pretty bad indeed, is that they’re not compatible with the Tesla superchargers.

The Taycan 4S I tested at my local Porsche center came from one previous owner with around 60.000 km on the meter. Importantly, given the many electronic issues many Taycans suffered from initially, the car was Porsche Approved with a 12-month guarantee. As can be seen, it was dark grey on black and quite well equipped with the larger battery package. In this configuration, it weighed in just shy of 2.600 kgs, without driver… The exterior colour suited the car well, but the black interior made the whole thing a bit somber. That said, black is the best colour if you want to hide plastics of which the Taycan’s interior has a lot, although they seem to be of better quality than on some other brands.

Walking around the car (which was parked next to a 992.1 on one side and my BMW 540i Touring on the other), it was easy to see that the Taycan was far more comparable in size to my Beamer than the 911. Checking the numbers later, it’s actually 2 cm longer than the G31 BMW at just under 5 metres, and 10 cm wider, at just under 2 metres width. Sitting behind the wheel, you also have a feeling of a big car.

They’re plenty of space in the front, far less so in the back, and not very much at all in the boot, although the Taycan has a relatively useful frunk to complement it. The interior otherwise looks nice and feels well put together, and given how well its screens are laid out and how good the tactile response is, to my surprise I didn’t miss physical buttons. Screens will never be better, but in the Taycan it’s at least almost as good.

Taking off means pressing the start button left of the steering wheel where traditionally the Porsche key should sit, and then a lever on the right hand side. The immediate feeling which, was then confirmed over the following drive, is again that of a big car that it takes some practice to place correctly. It feels very well balanced between front and rear, no doubt helped by the low center of gravity, but it’s nothing you throw into a corner like a 911. The steering is ok, although those complaining about the steering on the 991 generation that I mentioned in my post on the 911 Turbo S would be apalled by it, as it feels very synthetic and not that precise. I’d claim the steering in my 540i is better overall.

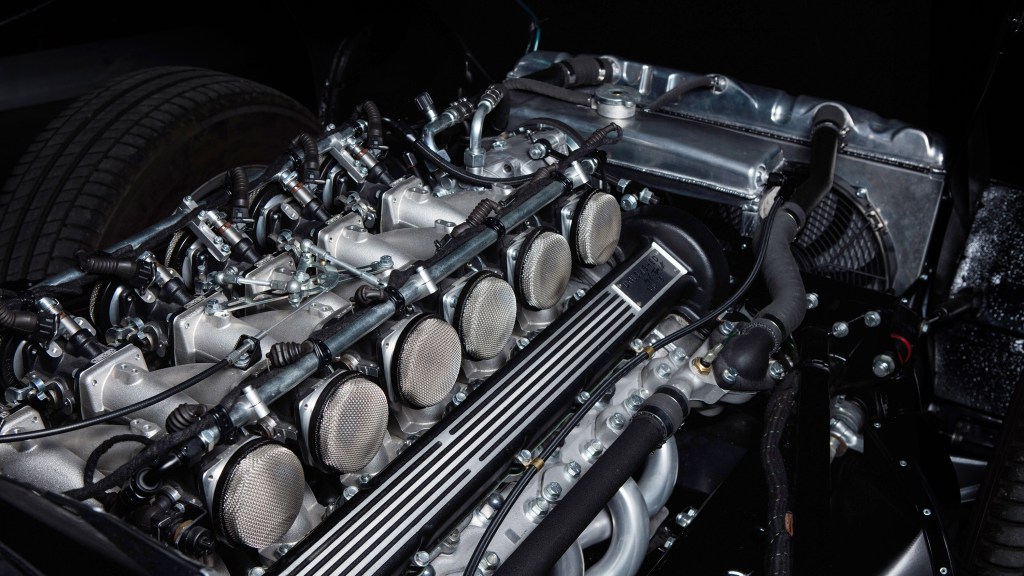

Even though the car is heavy, the 563 hp from the two electric engines (520 hp with the smaller battery pack) are plentiful, and no one needs more power than this. Unlike most EV’s, Porsche also uses a two-speed auto box sitting on the rear axle, with a short first gear to preserve the full acceleration and a longer second gear for higher top speed than a one-speed box would allow for. This also makes the electric engines run more efficiently as high speeds, saving energy – which again makes you wonder why the very sleek car doesn’t have a better range? The box is only noticeable when it shifts under hard acceleration, but that’s also what Porsche wants, trying to give the Taycan more of a mechanical feel.

The talented engineers in Zuffenhausen have also chosen a different braking and regeneration (regen) setup than most EV’s, again trying to make the Taycan feel more like a “normal” car. If you lift off the accelerator, the car will only coast (roll freely) with no regen, and thus no braking. When you brake however the regen kicks in fully, so that it’s only under heavy braking that you use the actual brakes. I would say that whether it was regen or actual braking, this is where you really feel how heavy the car is. The braking is solid enough, but it feels like the brakes have to work pretty hard to bring all of the 2.6 tons to a standstill. The km’s left in the range did however climb a little after some pretty heavy braking, so I guess it works.

This leads to the same conclusion as always with EV’s, that weight is the elephant in the room. My 540i station wagon weighs just under two tons or around 600 kgs less than the Taycan, a difference which roughly equals the weight of the battery pack. The Taycan is a fine car that drives really well for an EV, but it’s no sports car, and whoever calls this an electric 911 doesn’t know what they’re talking about.

Then again, that’s probably not a fair comparison given it has four seats and a decent luggage space. So what do you compare it to? To keep things simple and staying with BMW, if you want a sports car, an M3 or an M4 of a similar age are of similar size and price. They have about 100 hp less, but also weigh close to a ton (that’s 1000 kgs!) less. And if it’s more the GT aspect you’re after, a 4-series coupe in an equally stylish body will do the job with less power, but also far less weight. Of course there are other comparable models from Merc, Audi and others, and all are in the same price range.

Would I consider a Taycan? If for some reason I was forced to buy an EV, a used one like the one I drove would probably be a good choice. Whoever paid more than EUR 180.000 for it initially must be out of their mind or really convinced they were saving the planet (which, talking about EV’s, boils down to the same thing…). Therefore, unless someone forces me, I’ll just note that although impressive, the Taycan doesn’t move the needle neither in automobile terms, nor in Prosche terms. It’s not better, and much less spacious than my G31 540i Touring of the same age, or other comparable ICE cars.

The only needle the Taycan moves is that of the scale, and no weight-loss medicine beyond plastic is on the horizon for EV’s. That’s a nut even Porsche can’t crack. Driving the Taycan did one thing for me – it put the nagging feeling that I may have missed out on something to rest. When I take the trouble to test drive a car, I usually come away with a general feeling that it’s more exciting or better than my, by all means excellent 540i. The Taycan was the exception to the rule.