Long-term readers of this blog will probably have understood by now that I have a bit of a weakness for the mechanical age, and a fascination for the fantastic engineers and mechanics that built incredible automobiles in the age before computers and modern production methods had conquered the world. And when all this comes together in the lovely Italian car tradition, then that’s basically as good as it gets – if you ask me. This week we’ll look at what is perhaps the best demonstration of such inspired, but not fault-free engineering. We’ll do so with a bunch of engineers and designers that have already featured a couple of times on this blog, and actually also with an element that can be described as a lesson in good management. This week is about the Lamborghini Miura, small in size but very large in supercar tradition!

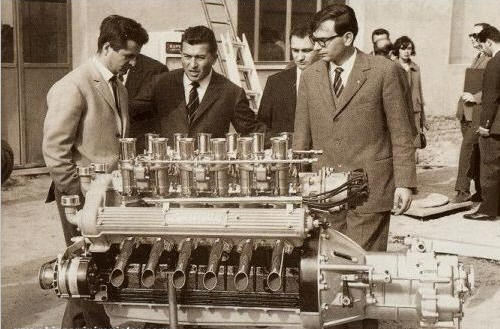

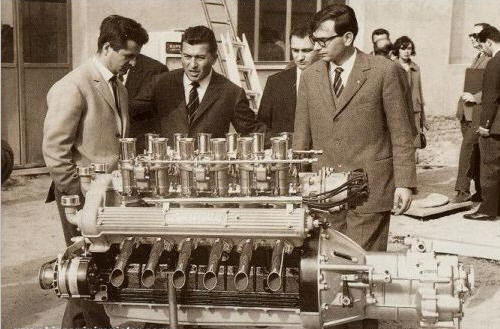

We’re back in the mid-60’s and Ferruccio Lamborghini, who has so far introduced three cars to the market, is set on building a better GT car than what Ferrari has to offer. Better in reliability but also better in parts, not recycling racing parts but rather with cutting edge technology. He doesn’t care much for low, loud and uncomfortable sports cars, but he’s keen on using the 12-cylinder engine our old friend Giotto Bizzarrini developed after he left Ferrari to set up his own company (I wrote about Bizzarrini a year ago, see here). That is indeed one hell of an engine which produced 350 hp and revved all the way up to 9800 rpm. That was a bit too much for Ferruccio and he therefore gave the engine to his two engineers Stanzani and Dallara (the latter also the chief engineer of the whole car) to reduce the rev range somewhat and make the engine more reliable. They did so, managing not to lose power in the operation (well, at least not officially), but it doesn’t change the fact that Bizzarrini indeed developed Lamborghini’s first 12-cylinder engine. In Ferruccio’s mind, the only thing missing now was a GT car to put it in.

What Ferruccio had at his disposal next to the engine was an enthusiastic group of young engineers and a designer we’ve also met before, Marcello Gandini, who had just been hired by Bertone. These young stars didn’t really share Ferruccio’s vision of the next Lambo being a GT car, and they were also heavy influenced by a certain Ford GT40 which at the time was big news in the US. The Ford was essentially a race car and heavily inspired by it, the engineers set off on the concept of a race car for the road rather than for the track. Ferruccio watched – and stood back, leaving the youngsters to it. That may not sound as impressive as it actually was. You see, at this time in 1965, in a world where age still counted for quite a lot, chief engineer Dallara was 29 years old, as was Stanzani. Soon-to-be designer Gandini was 27. In a world where old men still ruled, it was in other words a bunch of kids that designed the world’s first true supercar!

Dallara and Stanzani built a frame of a size suitable for the sports car they had in mind, but not necessarily suitable for a large V12. But rather than making the frame any larger, they turned the engine around and basically merged the transmission with it, as there was really nowhere else to put it. This was undoubtedly the tightest package around a V12 ever built and must have been a complete nightmare to work on as a mechanic – and quite a few mechanics would be doing so in subsequent years. The engineers put some wheels on the frame with the engine fitted, and now only the body was missing.

As mentioned, Ferruccio had let the youngsters work on this in peace and probably thought of the project as a good showcase for Lamborghini in general, and the coming GT car in particular. That’s also why the soon-to-be Miura was presented just like that, without a body, at the Turin car show in 1965. To Ferruccio’s great surprise, this was all it took for the first ten orders to come in. For the chassis that is, not for the coming GT car. It became obvious that a body was now needed, and the job was given to 27-year old Marcello Gandini who had started at Bertone two days earlier. He certainly didn’t sit around, but rather designed the Miura in as many days as he’d been employed. Thanks to this, the car in its final layout could be presented just five months later, at the Geneva Auto Show in 1966. 30 more orders came directly at the show, bringing the total to 40, growing to 75 by the end of the year.

Everyone including Ferruccio were obviously happy about the great success, but it also created a bit of stress in Sant’Agata. You see, at the time, Lamborghini employed all of… 78 people. Around 40 of those were engineers, and another 20 were apprentices. The first remark is that it’s remarkable to take an idea to production in as little as two years with such a small team, and even more so when you think of how complicated the Miura was. The second remark is that it would maybe have been good if those apprentices had been real mechanics, as was to be discovered later. For now, everyone was highly motivated, working long shifts all days of the week. Ferruccio was happy to let them work, brought them food at night, and continued to keep out of the way.

Unfortunately the quality of the first cars was problematic to say the least, and probably sensing this would be the case, Lamborghini made sure to deliver the first cars to Italian clients. As the cars came in for service, the clients were then taken to some very long lunches, giving the mechanics enough time not only to service the cars, but actually to do some quite fundamental changes and improvements to them. The first series was thus far from perfect, something that however improved with the updated Miura S in 1969, which produced 25 hp more and had a slightly wider track. Some quite serious problems did however persist during the Miura’s whole production run, including engines breaking down completely because of failing lubrification, and cars catching fire due to a less successful positioning of the tank. On the less than perfect side was also the heat caused in the cabin through the positioning of the engine, and the fact that the slightest touch of the accelerator made any conversation impossible. At the same time, that’s of course one of the Miura’s greatest thrills!

The Miura may not have been a race car but it certainly looked like one. It was also really fast for the time, meaning a 0-100 km/h of around 5.5-6 seconds and a top speed of around 280 km/h. The car was light, as was the front end, causing quite a few rollover accidents. The Miura S was replaced by the last version, the SV, in 1971, and even thought things kept improving, the Miura never became trouble-free. Finally in 1973 Ferruccio decided to pull the plug, but he didn’t do it as you may think, by firing the team behind the less than perfect Miura project. Instead he not only delegated the management of Lamborghini’s whole production to Stanzani, but he even accepted the latter’s demands not to interfere in the day to day work, and never to challenge his decisions. Stanzani, clearly a fan of the saying “when in trouble, double!” quickly moved on to create the Countach, a car no less exotic, but which would become much more well-known and much more legendary than the Miura (see here if you missed my review of it last year).

It may have been the first, but the Miura was thus by no means the perfect supercar. But honestly, how could it have been, with the limited resources and experience Lamborghini had at its disposal? That doesn’t change the fact that what a bunch of under-30-year-olds created in a few months was truly impressive in everything from idea to realization. It’s also a good lesson in management, illustrating that letting young people pursue their ideas usually produces good results! Accidents, fires and breaking engines has reduced the number of Miuras left on the road today from close to 500 produced to no more than a few dozen, and finding one isn’t easy. It’s also not cheap. For most of us, the Miura will thus remain something we may see at a car show, and otherwise a wonderful story of young talent from the golden age of the automobile!